Introduction

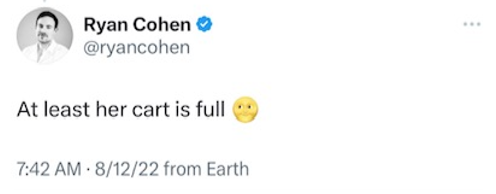

On July 27, 2023, the District Court for the District of Columbia ruled in In re Bed Bath & Beyond that certain securities fraud claims could proceed against the activist investor and “finfluencer” Ryan Cohen.1 Most notably, the court denied (in part) Cohen’s motion to dismiss claims that he had engaged in a “pump and dump scheme” in Bed Bath & Beyond’s securities.2 Specifically, the court ruled that the following tweet from Cohen could be reasonably interpreted as material and misleading.3

To be sure, this ruling arose in the context of a motion to dismiss and simply concluded that plaintiffs’ claims were plausible. Nevertheless, it also reflects growing concerns about the reach of finfluencers’ fraud and manipulation. A finfluencer is a person or entity—like Ryan Cohen—that has outsize influence on investor decisions through social media.4 Concerns generally focus on retail investors, in contrast to institutional investors.5 For example, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has issued multiple warnings against those who perpetrate pump-and-dump schemes on social media.6 And the North American Securities Administrators Association (NASAA), which “represents state and provincial securities regulators in the United States, Canada and Mexico” posted an “Informed Investor Advisory” on finfluencers in August 2022.7 Such warnings are widespread.8

This is due to the reach of finfluencers and the retail investors with which they engage, both of whom are shifting the stock market information ecosystem.9 Finfluencer and retail trading generate stock price movements that reflect their cultural values and preferences; information is increasingly disseminated through social media, and almost anyone can become an information broker in today’s stock markets.10

A further consequence is that finfluencers’ social media activity can generate stock price movements through followers’ trading activity even when that finfluencer has not made any statements containing information directly related to stock price or the underlying issuer’s prospects.11 For example, Cohen’s SEC filing which simply reiterated his existing holdings in Bed Bath & Beyond led to a 70% increase in the price of its stock because of his followers’ trading,12 and a tweet of a picture of himself with chopsticks up his nose13 sparked rampant discussion among his followers that the picture previewed an upcoming GameStop stock split (Cohen is the chair of GameStop’s board).14 As another example, Barstool Sports founder David Portnoy held a livestream where he randomly chose Scrabble tiles and traded according to the letter tiles he pulled.15 And, after Elon Musk, another powerful finfluencer, tweeted “GameStonk!!”16 in January 2021, GameStop’s stock price immediately rose around 40%.17

These actions are not obviously illegal. To be sure, stock prices reacted; however, no false information, nor, arguably, any new information was disseminated. This has created a gray area in finfluencer accountability because existing securities laws traditionally target clear deceit or manipulative intent.18 That is, existing securities laws primarily target lies.

In re Bed Bath & Beyond opens a path for seeking redress in this gray area: situations where no factually untrue statement has been made, but where a finfluencer’s followers are harmed nonetheless. This Piece argues that In re Bed Bath & Beyond applies a broadened materiality standard by considering the reasonable retail investor, not simply the reasonable investor. The reasonable retail investor has a particular relationship with finfluencers and relies primarily on social media to make investing decisions. Focusing on the reasonable retail investor makes it easier to hold finfluencers accountable for statements that are not clearly false or manipulative but which can be interpreted as such depending on the audience.

Part I of this paper discusses the reach of federal securities laws in deterring and punishing finfluencer wrongdoing. Part II examines In re Bed Bath & Beyond and related finfluencer litigation in the context of existing securities laws. Part III discusses the scope of the reasonable retail investor and the path forward. A brief conclusion follows.

I. The Existing Securities Law Regime

This Section summarizes existing securities laws and then describes a growing concern: a gray area has emerged with respect to finfluencer activity. Specifically, if a finfluencer does not facially engage in deceit or disseminate any clear information, existing laws do not clearly reach such activity.

A. Section 10(b), Rule 10b-5, and Section 9(a)

Fraud and manipulation are clearly prohibited by longstanding antifraud and antimanipulation provisions of the securities laws. Section 9(a) and Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as well as Section 10(b)’s accompanying Rule 10b-5, are the primary provisions used to punish and deter wrongdoing.19

Section 9(a)(2) outlaws effecting “a series of transactions” in a security (1) that “creat[e] actual or apparent active trading” or affect its price, (2) “for the purpose of inducing the purchase or sale of such security by others.”20 Because purchasing or selling a security will by definition create actual trading and will usually affect its price, Section 9(a)’s reach effectively hinges on the manipulator’s illicit purpose.

Section 10(b) outlaws the use of “any manipulative or deceptive device” in connection with trading a security in violation of an SEC rule.21 “[I]n connection with the purchase or sale of any security,” Rule 10b-5 makes the following unlawful:

(a) To employ any device, scheme, or artifice to defraud, (b) To make any untrue statement of a material fact or to omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made, in the light of the circumstances under which they were made, not misleading, or (c) To engage in any act, practice, or course of business which operates or would operate as a fraud or deceit upon any person[.]22

Rule 10b-5 has largely been used to police deceit and misrepresentation, and there is a large body of caselaw interpreting its scope.23 As the Supreme Court has stated, “Section 10(b) is aptly described as a catchall provision, but what it catches must be fraud.”24

B. The Finfluencer Gray Area

Pump and dump schemes—no matter how and on what form of media they are perpetrated—clearly fall within the purview of the prohibitions summarized above. This is because pump and dump schemes usually involve both identifiable misrepresentations or misstatements as well as manipulative or deceptive intent. A perpetrator purchases stock at a low price, shares false information about the issuer’s future prospects that prompts others to buy the stock, that buying activity inflates the price, and the perpetrator dumps their shares at a profit.25

Less clear is the application of the securities laws to situations where a finfluencer does not share false information or where a finfluencer arguably does not share any information at all. Consider Ryan Cohen, who simply restated an existing financial position in a routine SEC filing.26 As another example, GameStop’s stock price immediately rose around 40% after Elon Musk, another powerful finfluencer, tweeted “GameStonk!!”27 in January 2021.28 And, in early 2021, Keith Gill (better known as “Roaring Kitty” on Reddit.com) repeatedly posted comments arguing that GameStop was undervalued, followed by continuous iterations of “I like the stock,” which rallied retail investors to collectively drive GameStop’s stock price up from $4 to around $500 per share at one point.29

In these examples, no lie has been stated. In many cases, no substance at all was communicated. Materiality and whether the activity is intentionally misleading is difficult to prove, at least at first glance. Yet the ubiquity of finfluencing has created a growing concern that finfluencers can influence their followers and profit off their followers’ trading while steering clear of the securities laws. Retail investors are disproportionately harmed by this gray area activity.30 However, as the following sections demonstrate, the ruling in In re Bed Bath & Beyond opens a path for accountability in precisely these borderline situations.

II. Finfluencer Litigation

This Section begins by summarizing existing finfluencer litigation, which largely targets classic pump and dump schemes. It then provides a detailed analysis of the decision in In re Bed Bath & Beyond and shows how it provides a path to accountability in a case that could easily have escaped the reach of the securities laws.

A. Traditional Finfluencer Litigation

In re Bed Bath & Beyond is the latest in a series of cases and regulatory actions adjudicating the scope of wrongdoing in modern trading contexts.31 However, previous examples of finfluencer litigation primarily involve traditional pump and dump schemes.

For example, in December 2022, the SEC charged eight finfluencers with securities manipulation and fraud perpetrated on Twitter and Discord.32 According to the SEC, the defendants engaged in a pump and dump scheme by using “social media to amass a large following of novice investors and then took advantage of their followers by repeatedly feeding them a steady diet of misinformation, which resulted in fraudulent profits of approximately $100 million.”33 In February 2022, Michael M. Beck was charged for fraud using his Twitter handle @BigMoneyMike6.34 Steven Gallagher was arrested and charged the prior year with securities fraud, wire fraud, and manipulation.35 Using his Twitter handle @AlexDelarge6553 (named after the character in A Clockwork Orange), Gallagher engaged in a pump and dump scheme by tweeting false and misleading information.36

These cases all involve classic forms of securities fraud or manipulation. This is usually a pump and dump scheme whereby manipulators purchase stocks at a low price, share false information about the issuer’s future prospects that prompts others to buy the stock and inflate the price, at which point manipulators will sell their shares at a profit. The securities laws are well-equipped to handle pump and dump schemes regardless of the medium on which they are perpetrated. This is because the deceit (and related intent) is usually easily identifiable.

However, the district court ruling in In re Bed Bath & Beyond indicates that the securities laws may be flexible enough to handle wrongdoing in the finfluencer gray area, where statements may not be factually untrue, but which can be interpreted as such depending on the context and the particular beliefs held by one’s social media followers. The next section details how.

B. Ryan Cohen and Bed Bath & Beyond

Ryan Cohen, founder of Chewy.com and chair of GameStop’s board, is a powerful finfluence.37 He is known to his followers as “Papa Cohen,”38 has been referred to as a “meme stock king,”39 and his nearly 400,000 followers pay close attention to his tweets, seeking to divine hidden information on future corporate decisions or stock price movements.40

As with other finfluencers, even when Cohen’s social media activity contains no information directly related to the underlying issuer, stock prices move in response. Cohen himself has disavowed any informational intent behind his tweets: “I’m just being me; I’m just being myself[,]” and “I don’t want to speculate on how people interpret it.”41 But his followers remain undeterred. The Bed Bath & Beyond litigation provides a powerful example.

On August 12, 2022, in response to a CNBC story stating that Bed Bath & Beyond faced grim financial prospects, which included a picture of a woman with a shopping cart at Bed Bath & Beyond, Cohen tweeted the following42

Four days later, on August 16, 2022, Cohen filed a Schedule 13D with the SEC stating his current holdings in Bed Bath & Beyond, which included roughly a 10% stake in the company.43 These were essentially the same positions Cohen had previously disclosed in March 2022.44 Nevertheless, upon learning of Cohen’s 13D filing, retail investors purchased around $73 million in Bed Bath & Beyond in response, and the share price jumped nearly 70%.45 That same day, Cohen sold his entire stake in Bed Bath & Beyond, making profits of around $68 million.46 Once he disclosed the sale to the SEC, the price of Bed Bath & Beyond plummeted.47 Cohen, along with others, was subsequently sued by plaintiffs alleging that he manipulated Bed Bath & Beyond’s stock price and traded on insider information.48

At issue was the meaning of Cohen’s August 12, 2022 tweet containing the moon emoji:

Cohen argued that this tweet was neither material nor misleading.49 In rejecting Cohen’s argument, the Court explained that

“[s]ome online communities understand the smiley moon emoji to mean ‘to the moon’ or ‘take it to the moon.’ In other words, according to Plaintiff, Cohen was telling his hundreds of thousands of followers that Bed Bath’s stock was going up and that they should buy or hold. They did so, sending the price soaring.”50

The Court went on to explain “[t]he moon-emoji tweet was plausibly misleading because it was perceived ‘as a rallying cry to buy Bed Bath’s stock,’ even though Cohen had soured on Bed Bath.”51 Further, the Court explained that liability can attach to emojis “if they communicate an idea that would otherwise be actionable,” just like words.52

In its analysis, the Court focused on a subset of retail investors, meme investors, who “conceivably understood Cohen’s tweet to mean that Cohen was confident in Bed Bath and that he was encouraging them to act.”53 Quoting from the complaint, this was because “[i]n the meme stock ‘subculture,’ moon emojis are associated with the phrase ‘to the moon,’ which investors use to indicate ‘that a stock will rise.’”54 For support, the Court pointed to another opinion in which a district court deemed rocket ship emojis to mean the same thing.55 The Court then ruled that the meaning was actionable, i.e., plausibly material, because there was a “substantial likelihood that a reasonable investor would consider it important.”56

In other words, the Court assessed questions of materiality in today’s context of social media and finfluencing. It considered the “meme stock ‘subculture,’” which associated a moon emoji with the implication that “a stock will rise.”57 And it considered Cohen’s particular relationship with his followers, including his identity as a powerful finfluencer. The Court specifically noted that “[i]nvestors may have reasonably seen Cohen as an insider sympathetic to the little guy’s cause: He interacted with his followers on Twitter. He appeared to speak truth to power, criticizing ‘compensation for the Corporate Power Brokers,’” among other factors, “[s]o it was not crazy for retail investors to follow his lead.”58

The Court thus relied significantly on the specific relationship between a finfluencer (Cohen) and his followers and focused on how his followers would interpret the tweet given those followers’ specific priors, biases, and community beliefs. The Court did so for a communication that otherwise could be argued to contain no information at all. This is precisely the kind of finfluencer communication that falls within the gray area identified above. As the next section discusses, this opens a path for the reasonable retail investor to take primacy in future securities litigation against finfluencers.

III. The Reasonable Retail Investor

This Section first considers the materiality and reasonable investor standard in securities litigation. It then discusses the scope of the reasonable retail investor and its implications.

A. Materiality and the Reasonable Investor

The reasonable investor has a long history in securities laws. Central to a securities fraud action is the requirement of materiality. An actionable statement is one containing a “material fact” or omitting a “material fact” needed to make statements not misleading.59 Materiality is judged from the viewpoint of a “reasonable investor” considering the “total mix” of information.60

But who is the reasonable investor? The generally accepted test for materiality involves determining whether there is “a substantial likelihood that the disclosure of the omitted fact would have been viewed by the reasonable investor as having significantly altered the ‘total mix’ of information made available.”61 This determination has been a notoriously thorny task for courts, not least because the reasonable investor figure has eluded clear judicial or regulatory definition.62 This has led to inconsistency in adjudicating materiality against a vague and shifting notion of the “reasonable investor.”63

The reasonable investor inquiry is also highly context-dependent. The Supreme Court has repeatedly emphasized the fact-specific nature of the inquiry, explaining the need to consider the “full context” and naming factors such as “customs and practices of the relevant industry,” “surrounding text, including hedges, disclaimers, and apparently conflicting information.”64 The Court has also stated that “[t]he determination requires delicate assessments of the inferences a ‘reasonable shareholder’ would draw from a given set of facts and the significance of those inferences to him.”65

However, existing guidance does gesture to a reasonable rational investor, one who is relatively financially sophisticated (though not to the level of an investment professional), understands market concepts, and conducts financial and mathematical research on their own.66 This standard has been criticized as creating a mythical, aspirational figure that does not comport with reality, and certainly not with the reality of the average retail investor.67

B. The Reasonable Retail Investor

The ruling in In re Bed Bath & Beyond has opened a potential path forward for courts to consider the reasonable retail investor—especially when considering finfluencer activity. As stated above, to the extent a consensus exists, the “reasonable investor” has been largely understood by courts to mean the rational, fairly sophisticated investor.68 Similarly, in dominant stock market microstructure theory, retail investors are thought of as uninformed traders who act idiosyncratically and trade for reasons unrelated to information regarding the fundamental value of any given stock.69 In other words, traditional legal and economic theory has given little theoretical and practical thought to the retail investor’s role in capital markets.

Yet as I have shown elsewhere, retail investors are only growing in power and influence, an effect substantially amplified by the growth of finfluencing.70 Their impact is wide-ranging, from shifting the kinds of information reflected in stock prices to driving corporate reactions and capital flow.71

It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that a court would assess materiality from the perspective of a reasonable retail investor. This is precisely what the Court did in In re Bed Bath & Beyond. The Court pointed to “the meme stock subculture”72 that “understand[s] the smiley moon emoji to mean ‘to the moon’ or ‘take it to the moon,’”73 and “perceiv[es] [it] ‘as a rallying cry to buy Bed Bath’s stock,’ even though Cohen had soured on Bed Bath.”74 For support, the Court pointed to another opinion in which the Southern District of New York deemed rocket ship emojis to mean the same thing.75 Quoting from the complaint, this was because “[i]n the meme stock ‘subculture,’ moon emojis are associated with the phrase ‘to the moon,’ which investors use to indicate ‘that a stock will rise.’”76 The Court then ruled that the meaning was actionable, i.e., plausibly material, because there was a “substantial likelihood that a reasonable investor would consider it important.”77 The Court also considered Cohen’s particular finfluencing relationship with his followers: “[i]nvestors may have reasonably seen Cohen as an insider sympathetic to the little guy’s cause: He interacted with his followers on Twitter. He appeared to speak truth to power, criticizing ‘compensation for the Corporate Power Brokers[;]’” therefore, “it was not crazy for retail investors to follow his lead.”78

In other words, the Court did not consider Cohen’s tweet in a vacuum. It not only placed the tweet in the “total mix” of information, but it considered the “total mix” of information as would be salient to a retail investor (and even more specifically, a meme investor). Activity that might previously have been thought to occur near but not in violation of securities laws, such as tweeting emojis purportedly meant as a joke but which led to follower activity (even when that effect is arguably unintentional), might be deemed “material” when viewed through the lens of a reasonable retail investor.

C. A More Flexible Standard

Viewing materiality from the perspective of a reasonable retail investor opens a potential path forward for the millions of retail investors who have been or might be harmed by finfluencer activity that falls within the gray area of the securities laws. It places primacy on retail investors’ interpretation of finfluencer social media activity and calls into question courts’ tendency to apply a standard that assumes a rational and sophisticated reasonable investor. It is also supported by jurisprudence that emphasizes the importance of context.79 In doing so, it narrows a gap in securities oversight, demonstrating that existing securities laws can be flexible enough to deter and punish a significant portion of problematic finfluencer behavior.

When viewed through the lens of the reasonable retail investor, other fact patterns involving social media activity that may harm investors without literally being factually untrue may similarly lead to liability. For example, on January 26, 2021, Elon Musk, another powerful finfluencer, tweeted “GameStonk!!”80 GameStop’s stock price immediately rose around 40%.81 Musk has also previously tweeted statements that “Tesla stock price is too high imo”82 and “Am considering taking Tesla private at $420. Funding secured.”83 Tesla’s stock price saw dramatic short-term swings as a result and a number of SEC actions and civil lawsuits have already followed.84 As another example, Kevin Paffrath, a YouTube finfluencer known as MeetKevin, has launched an exchange-traded fund called the The Meet Kevin Pricing Power ETF.85 If a finfluencer such as Paffrath simply encourages his followers to buy his ETF, perhaps using a moon emoji, such activity could be seen as implicitly stating that his ETF will rise.

These are just a few potential ways in which the reasonable retail investor could help vindicate the harms suffered by many retail investors. As prices increasingly reflect retail trading patterns, finfluencers who impact those trading patterns may be increasingly liable for resulting harm. If stronger protections against finfluencers exist, retail investors may feel more comfortable participating in the stock market, which will have broader macroeconomic benefits.86 It might also promote additional information sharing between finfluencers, corporations, and retail investors.87 Most importantly, it will better motivate finfluencers to take greater care in their communications—just as corporations do—and support better information generation and dissemination.

Conclusion

The reasonable retail investor provides a viable path forward for the millions of retail investors who have been or might be harmed by finfluencer activity that falls in the gray area of the securities laws. Retail investors who lost significant amounts of money after Cohen disclosed his sale in Bed Bath & Beyond stock have found a plausible path forward. Eventually, others might as well.

- In re Bed Bath & Beyond Corp. Sec. Litig., No. 1:22-cv-2541, 2023 WL 4824734 (D.D.C. July 27, 2023). The SEC is also investigating Cohen’s sale of Bed Bath & Beyond’s stock in August 2022. Dave Michaels & Lauren Thomas, SEC Probes Ryan Cohen’s Bed Bath & Beyond Trades, Wall St. J. (Sept. 7, 2023, 5:45 AM), https://www.wsj.com/business/retail/sec-probes-ryan-cohens-bed-bath-beyond-trades-e9f35b81 [https://perma.cc/6CMT-9YGV]. ↩︎

- In re Bed Bath, 2023 WL 4824734, at *1, *12. ↩︎

- Id. at 2. ↩︎

- For a full explication of this phenomenon, see generally Sue S. Guan, The Rise of the Finfluencer, 19 N.Y.U. J.L. & Bus. 489 (2023) [hereinafter Finfluencer]. ↩︎

- The term retail investors or retail traders is used here to refer to those who directly trade in stock for individual accounts, as distinguished from institutional investors, who trade for institutional accounts. See Adam Hayes, Retail Investor: Definition, What They Do, and Market Impact, Investopedia, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/retailinvestor.asp [https://perma.cc/3PUD-L4R3] (Jan. 12, 2024) (defining retail investors as “non-professional market participants who generally invest smaller amounts than larger, institutional investors”); Donald C. Langevoort, The SEC, Retail Investors, and the Institutionalization of the Securities Markets, 95 Va. L. Rev. 1025, 1025 (2009) (distinguishing retail investors from institutional investors as “individuals and households”). ↩︎

- See Social Media and Investment Fraud—Investor Alert, U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n (Aug. 29, 2022), https://www.sec.gov/oiea/investor-alerts-and-bulletins/social-media-and-investment-fraud-investor-alert [https://perma.cc/PML8-RFJR] (cautioning against false or misleading information on social media and describing common scams); Investor Bulletin: Social Sentiment Investing Tools—Think Twice Before Trading Based on Social Media, U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n (Apr. 3, 2019), https://www.investor.gov/introduction-investing/general-resources/news-alerts/alerts-bulletins/investor-bulletins-18 [https://perma.cc/C2SK-B65H] (detailing risks of social sentiment investing tools, which analyze data from social media). ↩︎

- The North American Securities Administrators Association issued an advisory stating that,

A finfluencer is a person who, by virtue of their popular or cultural status, has the ability to influence the financial decision-making process of others through promotions or recommendations on social media. They may influence potential buyers by publishing posts or videos to their social media accounts, often stylized to be entertaining so that the post or video will be shared with other potential buyers. The financial influencer may be compensated by the business offering the product or service, the platform on which the message appears, or an undisclosed financier. While there is nothing new about marketers paying celebrities to endorse their products, what IS different is that such breezy and hyper-emotional endorsements are being made in what is otherwise a very regulated industry with stringent rules about performance claims and disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. Remember, investment promoters generally must provide potential investors with all information relevant to making an informed investment decision. Finfluencers are testing the limits of what is considered regulated investment advice and protected free speech.”

NASAA, Informed Investor Advisory: Finfluencers (Aug. 2022), https://www.nasaa.org/64940/informed-investor-advisory-finfluencers/ [https://perma.cc/HMW2-MP5B]. ↩︎ - See, e.g., CA Dep’t of Fin. Prot. & Innovation, Social Media Finfluencers—Who Should You Trust? (Oct. 5, 2022), https://dfpi.ca.gov/2022/10/05/social-media-finfluencers-who-should-you-trust/ [https://perma.cc/3QRJ-MLV3] (describing risks associated with information disseminated by finfluencers); VA State Corp. Comm’n, SCC Cautions Virginians About Social Media “Finfluencers” Providing Financial Advice (Sept. 8, 2022), https://scc.virginia.gov/newsreleases/release/SCC-Cautions-Virginians-About-Online-Finfluencers [https://perma.cc/F2LZ-Q5AX] (providing ways to minimize risks as social media replaces traditional investing information sources); D.C. Dep’t of Ins., Sec. & Banking, Beware of Financial Influencers, https://disb.dc.gov/page/beware-financial-influencers [https://perma.cc/A9HK-SHFQ] (cautioning against finfluencers’ financial advice). ↩︎

- See generally Guan, Finfluencer, supra note 4. ↩︎

- See id. at 497-508 (providing a taxonomy of finfluencers, from celebrity finfluencers to ordinary investor finfluencers). ↩︎

- See id. at 508-27 (gathering evidence of finfluencer price impact and providing a theoretical analysis of it). ↩︎

- In re Bed Bath & Beyond Corp. Sec. Litig., No. 1:22-cv-2541, 2023 WL 4824734, at *7, *11 (D.D.C. July 27, 2023). ↩︎

- Ryan Cohen (@ryancohen), Twitter (July 19, 2021, 7:48 PM), https://twitter.com/ryancohen/status/1417315406272864258?lang=en [https://perma.cc/LX2H-QYK6]. ↩︎

- See Miriam Gottfried & Caitlin McCabe, GameStop’s Ryan Cohen Wants to Be More Than a Meme-Stock King, Wall St. J. (Nov. 19, 2022, 12:00 AM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/gamestops-ryan-cohen-wants-to-be-more-than-a-meme-stock-king-11668834015 [https://perma.cc/V66D-6SKG] (describing Cohen’s background and the reaction of his followers to his Tweet); Joe Fonicello, Ryan Cohen Splits Chopsticks 2:1; PG-13, GMEdd (July 20, 2021), https://www.gmedd.com/tw/ryan-cohen-splits-chopsticks-21-pg-13/ [https://perma.cc/BD2J-U8BF] (engaging in speculation on the meaning of Cohen’s chopsticks tweet). ↩︎

- Akane Otani, The New Stock Influencers Have Huge—and Devoted—Followings, Wall St. J. (Mar. 21, 2021, 5:30 AM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-new-stock-influencers-have-hugeand-devotedfollowings-11616319001 [https://perma.cc/54KS-R7H3]; see also Matt Wirz, Meme–Stock Traders Embrace Avaya Despite Wall Street Fears, Wall St. J. (Sept. 19, 2022, 8:00 AM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/meme-stock-traders-embrace-avaya-despite-wall-street-fears-11663540636 [https://perma.cc/R3UV-52UD] (noting activist investor Theo King’s meme trader followers). ↩︎

- Elon Musk (@elonmusk), Twitter (Jan. 26, 2021, 4:08 PM), https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1354174279894642703?lang=en [https://perma.cc/38QX-9QD2]. ↩︎

- See GameStop Corp. (GME), Yahoo! Fin., https://finance.yahoo.com/quote/GME?p=GME [https://perma.cc/LV5C-2692] (last visited Dec. 1, 2023) (depicting a graph of GameStop Corporation’s stock value). ↩︎

- See infra note 23 and accompanying text. ↩︎

- Securities Exchange Act of 1934, 15 U.S.C. §§ 78i(a)(2), 78j(b); Employment of Manipulative and Deceptive Devices, 17 C.F.R. § 240.10b-5 (2023); see also Merritt B. Fox, Lawrence R. Glosten, & Sue S. Guan, Spoofing and Its Regulation, 2021 Colum. Bus. L. Rev. 1244, 1293 (“[S]ections 9(a)(2) and 10(b) of the Securities and Exchange Act remain the primary tools used to police misconduct.”); Christine Hurt, Socially Acceptable Securities Fraud 7 (Aug. 4, 2023) (unpublished manuscript) (noting the expansive reliance on Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 in bringing securities fraud actions). ↩︎

- 15 U.S.C., § 78i(a)(2). ↩︎

- Id. § 78j(b). ↩︎

- Employment of Manipulative and Deceptive Devices, 17 C.F.R. § 240.10b-5 (2023). ↩︎

- See Chiarella v. United States, 445 U.S. 222, 234-35 (1980) (“Section 10(b) is aptly described as a catchall provision, but what it catches must be fraud.”); Schreiber v. Burlington N., Inc., 472 U.S. 1, 7-8 (1985) (“Congress used the phrase ‘manipulative or deceptive’ in § 10(b) as well, and we have interpreted ‘manipulative’ in that context to require misrepresentation.”); Ernst & Ernst v. Hochfelder, 425 U.S. 185, 199 (1976) (“[T]he word ‘manipulative’ . . . is and was virtually a term of art when used in connection with securities markets. It connotes intentional or willful conduct designed to deceive or defraud investors by controlling or artificially affecting the price of securities.”). ↩︎

- Chiarella, 445 U.S. at 234-35. ↩︎

- See U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n, Pump and Dump Schemes, https://www.investor.gov/introduction-investing/investing-basics/glossary/pump-and-dump-schemes [https://perma.cc/8VW9-ZHB7] (last visited Nov. 21, 2023) (describing the scheme). ↩︎

- See Cohen, supra note 13. ↩︎

- Elon Musk, supra note 16. ↩︎

- See GameStop Corp. (GME), supra note 17 (illustrating GameStop’s stock price rise). ↩︎

- See Nathaniel Popper & Kellen Browning, The ‘Roaring Kitty’ Rally: How a Reddit User and His Friends Roiled the Markets, N.Y. Times (Jan. 29, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/29/technology/roaring-kitty-reddit-gamestop-markets.html [https://perma.cc/5WNZ-TWCR] (detailing “Roaring Kitty’s investment in Gamestop); Noel Randewich, GameStop Fan ‘Roaring Kitty’ to Tell Congress: ‘I Like the Stock,’ Reuters (Feb. 17, 2021, 6:24 PM), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-retail-trading-testimony-reddit-idUSKBN2AH2Y2 [https://perma.cc/7LCE-6AZD] (discussing Roaring Kitty’s repeated use of the phrase “I like the stock”). ↩︎

- See Ali Kakhbod et al., Finfluencers 1 (July 5, 2023) (unpublished manuscript) (using a dataset of over 29,000 finfluencers on StockTwits, to show that more than half have negative skill and to demonstrate that unskilled and antiskilled finfluencers “have more followers, more activity, and more influence on retail trading than skilled finfluencers”). There are legitimate concerns with regulatory paternalism vis-à-vis retail investors. See Christine Hurt, Socially Acceptable Securities Fraud 25 (Aug. 4, 2023) (unpublished manuscript) (“[R]egulation can do little to battle or protect the ignorant, misguided, or overconfident.”); Jill E. Fisch, GameStop and the Reemergence of the Retail Investor, 102 B.U. L. Rev. 1799, 1825 (2022) (“Regulating with the objective of preventing unwise investing decisions is paternalism.”). ↩︎

- See, e.g., In re Tesla, Inc. Sec. Litig., 477 F. Supp. 3d 903, 907 (N.D. Cal. 2020) (detailing an earlier plaintiff shareholder’s suit based on allegedly false social media statements by Elon Musk). ↩︎

- Press Release, U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n, SEC Charges Eight Social Media Influencers in $100 Million Stock Manipulation Scheme Promoted on Discord and Twitter (Dec. 14, 2022), https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2022-221 [https://perma.cc/G4F4-EZ5C]. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- See Complaint at 2, SEC v. Beck, No. 2:22-cv-00812-FWS-JC, 2022 WL 19333272 (C.D. Cal. Feb. 7, 2022) (“Defendant Michael M. Beck . . . used his Twitter platform, where he had as many as 3 million followers, to promote and encourage people to buy eight microcap stocks—all without disclosing that he planned to sell, or in some instances was personally selling, his own holdings of the same stocks (a practice known as ‘scalping’.”)). ↩︎

- Complaint, United States v. Gallagher, No. 21-mag-10220 (S.D.N.Y. filed Oct. 25, 2021); see Complaint, SEC v. Gallagher, No. 1:21-civ-8739, 2023 WL 6276688 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 26, 2021) (detailing Gallagher’s various violations of securities laws). ↩︎

- See Complaint, United States v. Gallagher, supra note 35, at 4 (“[Gallagher] has operated a fraudulent pump-and-dump scheme that employed a variety of tactics to defraud individual, non-professional investors—so-called ‘retail investors.’”). ↩︎

- For a full survey of finfluencer types and activity, see Guan, Finfluencer, supra note 4, at 497-508. Finfluencers are not new to stock markets and range from those such as Jim Cramer on CNBC to Elon Musk to Kevin Paffrath, a YouTube finfluencer known as MeetKevin who has launched his own ETF, the MeetKevin Pricing Power ETF. Id. They are shifting the stock market information ecosystem and provide powerful coordination mechanisms across their followers that result in significant stock price activity. See id. at 508-31 (gathering evidence of finfluencer price impact and providing a microstructure driven analysis of finfluencer price impact). ↩︎

- Caitlin McCabe, The Meme Lords Who Are Taking over the C-Suite, Wall St. J. (Aug. 27, 2021, 5:30 AM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-meme-lords-who-are-taking-over-the-c-suite-11630056603?mod=series_exchangeinternetpackage [https://perma.cc/WX62-DEXT]. ↩︎

- Gottfried & McCabe, supra note 14; Amanda Winograd, How GameStop’s Ryan Cohen Became the ‘Meme King’, CNBC, https://www.cnbc.com/2023/06/07/how-gamestops-ryan-cohen-became-the-meme-king.html [https://perma.cc/ZZY3-VUXZ] (Sep. 28, 2023, 7:00 AM). ↩︎

- See McCabe, supra note 38; Gottfried & McCabe, supra note 14 (noting many investors search for clues in Cohen’s social media posts for future stock price indications); Fonicello, supra note 14 (“Speculative investors were quick to draw assumptions as to what a deeper meaning of the tweet could entail, largely rooted in the odd text and the split chopsticks.”); see also Ryan Cohen, supra note 13 (evidencing followers speculating about the meaning of Cohen’s tweets). ↩︎

- Gottfried & McCabe, supra note 14. ↩︎

- CNBC (@CNBC), Twitter (Aug. 12, 2022, 7:04 AM),https://twitter.com/CNBC/status/1558046723053953025 [https://perma.cc/DMM2-JGXU]; Ryan Cohen (@ryancohen), Twitter (Aug. 12, 2022 10:42 AM), https://twitter.com/ryancohen/status/1558101541453795329 [https://perma.cc/5F8K-7P59]. ↩︎

- In re Bed Bath & Beyond Corp. Sec. Litig., No. 1:22-cv-2541, 2023 WL 4824734, at *1-2 (D.C.C. July 27, 2023). A Schedule 13D filing is required when an investor acquires more than five percent of a company’s stock. 17 C.F.R. § 240.13d-1 (2010). ↩︎

- Caitlin McCabe, Bed Bath & Beyond Stock Price Soars More than 60% on Ryan Cohen’s Stake, Wall St. J. (Mar. 7, 2022, 4:31 PM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/bed-bath-beyond-stock-price-soars-premarket-on-ryan-cohens-stake-11646652094?mod=article_inline [https://perma.cc/AY7X-MD84]. ↩︎

- See Yun Li & Lauren Thomas, Bed Bath & Beyond Soars as Much as 70% as Meme Traders Talk up Ryan Cohen’s Call Options Purchase, CNBC (Aug. 16, 2022, 12:16 PM),https://www.cnbc.com/2022/08/16/bed-bath-beyond-soars-70percent-as-meme-traders-bet-on-ryan-cohen.html#:~:text=Shares%20of%20Bed%20Bath%20%26%20Beyond,ended%20the%20session%2029%25%20higher [https://perma.cc/6ULW-WQLL] (explaining how information about Cohen’s call options led to a surge in trading volume of Bed Bath & Beyond Stock). ↩︎

- See In re Bed Bath, 2023 WL 4824734, at *1-2 (noting how Cohen’s actions increased the stock price just before he sold his stake). ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id. at *1. The SEC is also investigating Cohen’s sale of Bed Bath & Beyond’s stock as of 2023. Michaels & Thomas, supra note 1. ↩︎

- In re Bed Bath, 2023 WL 4824734, at *5. ↩︎

- Id. at *2. ↩︎

- Id. at *5. ↩︎

- Id. at *6. The Court explained why emojis are as actionable as any statement:

Emojis are symbols. Like symbols, language can be ambiguous. . . . Context and tone help elucidate meaning. Just because language can be ambiguous does not mean it is not actionable or capable of being correctly understood.

So too with symbols. People use symbols as “a primitive but effective way of communicating ideas.” Sometimes, symbols are ambiguous. If you texted your friend to ask him to have dinner with you and he responded with the steak emoji, you might reasonably wonder if he wanted to go to a steak house or fire up the grill. But like language, a symbol’s meaning may be clarified by “the context in which [the] symbol is used.” So if you knew that friend had sworn off restaurants, then you could be more certain that he was up for a cookout.

Id. at *5 (citations omitted). ↩︎ - Id. at *6. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id. at *5 (citing Friel v. Dapper Labs, Inc., No. 21-cv-5837, 2023 WL 2162747, at *17 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 22, 2023)). ↩︎

- Id. at *6 (citations omitted). ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Employment of Manipulative and Deceptive Devices, 17 C.F.R. § 240.10b-5(b) (2023). ↩︎

- The general test involves determining whether there is “a substantial likelihood that the disclosure of the omitted fact would have been viewed by the reasonable investor as having significantly altered the ‘total mix’ of information made available.” TSC Indus., Inc. v. Northway, Inc., 426 U.S. 438, 449 (1976). See also Hurt, supra note 30, at 19 (“The well-accepted, but not particularly useful, test for whether a particular fact about an issuer is material is whether a reasonable investor would find the fact important given the ‘total mix’ of information available about the issuer.”); Amanda M. Rose, The ‘Reasonable Investor’ of Federal Securities Law, 43 J. Corp. L. 1, 86-88 (2017) (detailing the development of the materiality standard). ↩︎

- TSC Indus., 426 U.S. at 449. ↩︎

- See Rose, supra note 60, at 88-90 (“Notwithstanding the important role the reasonable investor plays in federal securities regulation, ‘courts have not spoken with one clear voice on its identity,’ leaving the figure ‘anonymous, elusive, and the subject of much inquiry.’”). ↩︎

- Id. at 89. ↩︎

- Omnicare, Inc., v. Laborers Dist. Council Constr. Indus. Pension Fund, 575 U.S. 175, 190 (2015). ↩︎

- TSC Indus., 426 U.S. at 450. ↩︎

- See Hurt, supra note 30, at 21 (footnote omitted) (“[J]ust as the reasonable person is not average and is probably more careful than the average person, the reasonable investor is probably not the average retail investor and may be an aspirational model of a rational investor”); Rose, supra note 60, at 89-90 (gathering sources and noting that most scholars conceptualize the reasonable investor as a rational actor who “grasps market fundamentals—for example, the time value of money, the peril of trusting assumptions, and the potential for unpredictable difficulties to derail new products”); Tom C.W. Lin, Reasonable Investor(s), 95 B.U. L. Rev. 461, 466-67 (2015) (explaining that while the reasonable investor’s characteristics have not been agreed upon by courts, regulators, or commentators, the “leading paradigm” casts the reasonable investor as “the idealized, perfectly rational actor of neoclassical economics”); Joan MacLeod Heminway, Female Investors and Securities Fraud: Is the Reasonable Investor a Woman?, 15 Wm. & Mary J. Women & L. 291, 297 (2009) (“Decisional law and the related literature support the view that the reasonable investor is a rational investor . . . .”). ↩︎

- See Rose, supra note 60, at 89-92 (chronicling longstanding criticism of this conception); Donald C. Langevoort, Taming the Animal Spirits of the Stock Markets: A Behavioral Approach to Securities Regulation, 97 Nw. L. Rev. 135, 173 (2002) (describing the SEC’s “awkward myth-story in which . . . the typical retail investor is very much an earnest and rational person, but with bounded capacity”). ↩︎

- See supra note 66 (listing various descriptions of the “reasonable investor”). ↩︎

- See Merritt B. Fox et al., The New Stock Market 62 (2019) (“Uninformed traders buy and sell shares without possession of information that allows a more accurate appraisal of the stock’s value than the assessment implied by current market prices.”). For example, an individual investor may need to sell stock in order to pay an upcoming bill. This is an example of an idiosyncratic reason to buy or sell stock that is unrelated to information about the underlying issuer. See id. (“One possible motivation for an uninformed trade is that purchase of the share and its later sale are a way of saving: deferring consumption from the time of the purchase to the time of the sale.”). ↩︎

- See generally Sue S. Guan, Meme Investors and Retail Risk, 63 B.C. L. Rev. 2053 (2022) [hereinafter Meme Investors] (analyzing the impact of retail trading on prices and markets); Guan, Finfluencer, supra note 4, at 508-31 (describing the effects of finfluencers on prices and information). ↩︎

- See Guan, Meme Investors, supra note 70, at 2089-2102 (describing the effects of “coordinated retail risk” on the market); Guan, Finfluencer, supra note 4, at 531-43 (analyzing how finfluencer activity affects other market participants’ incentives and capital flow). ↩︎

- In re Bed Bath & Beyond Corp. Sec. Litig., No. 1:22-cv-2541, 2023 WL 4824734, at *6 (D.D.C. July 27, 2023). ↩︎

- Id. at *2. ↩︎

- Id. at *5. ↩︎

- Id. at *5 (citing Friel v. Dapper Labs, Inc., No. 21-cv-5837, 2023 WL 2162747, at *17 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 22, 2023)). ↩︎

- Id. at *6. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- See supra discussion Part III.A. ↩︎

- Elon Musk, supra note 16. ↩︎

- GameStop Corp. (GME), supra note 17. ↩︎

- Elon Musk (@elonmusk), Twitter (May 1, 2020, 11:11 AM), https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1256239815256797184?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw [https://perma.cc/JVG8-9SQ2]. ↩︎

- Elon Musk (@elonmusk), Twitter (Aug. 7, 2018, 4:48 PM), https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1026872652290379776 [https://perma.cc/UTL6-XN37]. ↩︎

- See In re Tesla, Inc. Sec. Litig., 477 F. Supp. 3d 903, 922 (N.D. Cal. 2020) (illustrating a securities class action against Tesla and Musk for securities fraud related to his “funding secured” tweet). The jury found in favor of Musk, and the district judge suggested that defendants presented sufficient evidence to demonstrate that the tweets were not “materially false.” In re Tesla, Inc., Sec. Litig., No. 18-CV-04865-EMC, 2023 WL 4032010, at *7-8 (N.D. Cal. Apr. 1, 2022). ↩︎

- See The Meet Kevin Pricing Power ETF, https://www.mketf.com/ [https://perma.cc/JXX2-3APD] (last visited Dec. 2, 2023) (describing the fund as an “actively managed exchange-traded fund (‘ETF’) that seeks to achieve its investment objective by investing primarily in the U.S.-listed equity securities of Innovative Companies”); see also Spencer Jakab, Meet Kevin, the ETF, Wall St. J. (Nov. 29, 2022, 12:42 PM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/meet-kevin-the-etf-11669743728 [https://perma.cc/E6U8-MUQ5] (describing Paffrath’s rise on social media as a finfluencer). ↩︎

- See Fox, supra note 19, at 1290-91 (explaining that negative market perception may lead to a reduction in retail market participation); Michael Lewis, Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt 200-01 (2014) (linking perceptions of market unfairness with low stock ownership); Editorial, The Hidden Cost of Trading Stocks, N.Y. Times (June 22, 2014), http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/23/opinion/best-execution-and-rebates-for-brokers.html [perma.cc/D45P-EWLT] (describing differential treatment for sophisticated and ordinary investors who participate in the stock market). ↩︎

- See Guan, Finfluencer, supra note 4, at 536-50 (discussing ways in which corporations react to retail investor and finfluencer activity and suggesting that finfluencers can improve communication between retail investors and corporations). ↩︎